pixabay.com © Eluj

Challenges and solution strategies

Overview

- The "DeMiCo" project analyses why so many well-educated people from Central and Eastern Europe work in underqualified jobs in Austria.

- The project focuses on barriers and difficulties faced by jobseekers from Hungary, Romania and the Czech Republic, as well as possible solution strategies..

- Preliminary findings show how institutional framework conditions, experiences of discrimination and German language skills have a significant impact on lived realities of those affected.

Citizens from countries that joined the EU in 2004 face numerous obstacles when looking for work in Austria. Researchers at the University of Vienna interviewed those affected about their perceptions and agency regarding these problems, which they next interpreted in conjunction with institutional labour market structures.

In research, we speak of “deskilling” when people work below their professional abilities and skills, i.e., their acquired qualifications. Statistics clearly show that people with foreign citizenship are affected by this far more frequently than Austrians. However, little qualitative research has examined this to date. How are these deskilling processes perceived by the migrants themselves? What experiences of discrimination do people have and what solution strategies do they use?

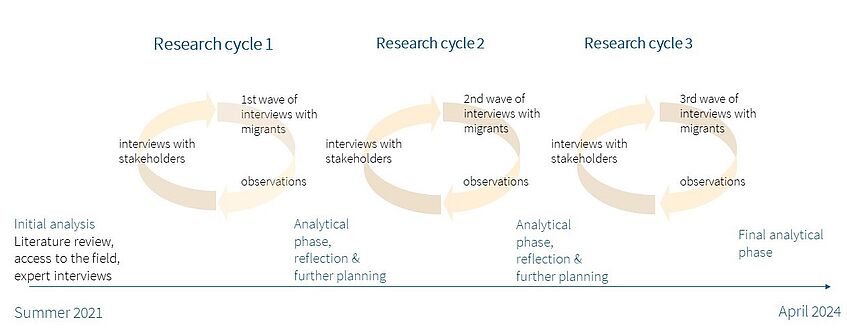

Elisabeth Scheibelhofer, Clara Holzinger and Anna-Katharina Draxl from the Department of Sociology are investigating this as part of the FWF-funded research project "Deskilling of 'new' EU migrants" (DeMiCo). DeMiCo focuses on the lived realities for highly qualified people from Hungary, Romania and the Czech Republic who live and work in Vienna but obtained their degrees abroad. The individual action and solution strategies that migrants use to manage obstacles and disadvantages when looking for work are central to the project. These are collected in collaboration with interpreters through interpretative interviews.

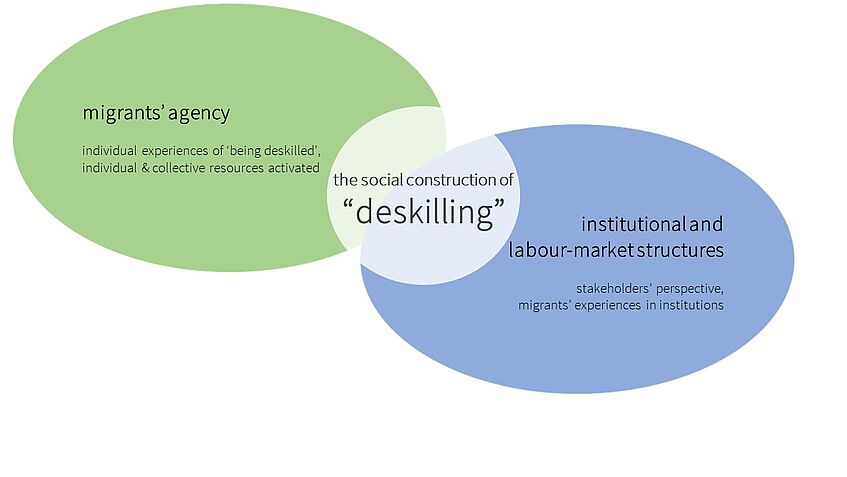

© DeMiCo

Additionally, institutional actors such as representatives from the Chamber of Commerce (WKO) and the Public Employment Service (AMS) are also interviewed and ethnographic observations are made to understand the migrants' ability to act within a larger institutional network. Preliminary findings show that, in addition to structural and institutional framework conditions, social networks, German language skills and experiences of discrimination and racism also play a major role in the realities of the lives of people affected by deskilling.

People come to Austria with certain ideas and are then confronted with reality

An illustrative case study, says Clara Holzinger, is shown with Estera (name changed by the editors), a young woman from Romania. Estera is a qualified healthcare and nursing professional who came to Vienna for work: "You'd think that would be very much in the interests of Austria, which has an acute nursing shortage and is desperately looking for trained nurses," says Holzinger. Estera moved to Vienna with her partner and a small child and tried to have her nurse training recognised here—a particularly lengthy and complex process with many bureaucratic barriers. Until her nostrification was finally completed—a process required to recognize Estera's training as equivalent to qualifications achieved in Austria—she worked as an underpaid care assistant. Reconciling paid work, care work (care work for her own environment, such as bringing up children, housework, caring for relatives), German courses and pursuing nostrification was almost impossible. Estera was on the verge of giving up and returning to Romania. With the support of family members and a lot of self-motivation, such as learning German on her own—often in the middle of the night—she ultimately managed to work as a nurse in Vienna despite having faced many barriers along the way.

Reproduction of hierarchies

Looking into the "black box" of deskilling processes requires qualitative interviews that are loosely structured and give interviewees space to present their own view of the phenomenon in detail. There is no questionnaire—the migrants have opportunity to tell their story in the interviews freely and openly and to develop their own thoughts. "The interviewees tell us about their lives in a very short amount of time. It creates a new situation that does something to both the interviewees and us as researchers," explains Clara Holzinger. Influenced by social power relations, the specific interview situation is created jointly by the parties involved and thus encourages researchers and interviewees to view and reflect on a phenomenon from different perspectives. This makes new insights possible. This type of dialogue can only take place in a trusting atmosphere with as few hierarchies as possible between the interviewees and researchers.

© DeMiCo

The fact that hierarchies cannot be completely dismantled—despite all efforts made by the researchers—is particularly evident when it comes to experiences of discrimination. "We start the interview with the hypothesis that our interviewees are affected by racism because we live in a society characterised by racism," explains Anna-Katharina Draxl. However, this topic is often avoided or denied in the interviews. According to the researchers, this has to do with the hierarchies of the people present: "We don't just come into the conversation as researchers, but also as white-constructed Austrians without a migration background," adds Clara Holzinger. This results in a power dynamic on several levels. On the one hand, the researchers have the power to report on the experiences and realities of migrants' lives. On the other hand, they live in very different realities, as project leader Elisabeth Scheibelhofer points out: "We do not only have a prestigious profession as scientists, but we also go through our everyday lives without language barriers or an appearance that does not conform to the norm influencing how we are perceived and treated." According to the researchers, these elements must always be considered when it comes to understanding why experiences of discrimination are not always openly addressed by those affected.

The role of language

One approach to reducing hierarchies with regard to language is central to the project: "We live in a multilingual society—we deliberately want to reflect this in DeMiCo," explains Elisabeth Scheibelhofer. In the project, the interviewees are therefore free to choose the language in which they want to conduct the interview—whether in German, English or their first language. "This multilingual approach is a key message and an innovative aspect of DeMiCo," the researcher continues. The fact that sufficient budgets for professional interpreters and translators are calculated and also funded is unfortunately not yet standard in research and the methodological implications thereof have so far been insufficiently addressed in the sociological literature. DeMiCo therefore aims to make an innovative contribution to the further development of research methods in the context of societal multilingualism. Hence, the research team pursues a cooperative approach that involves close collaboration with professional interpreters and translators, who are trained in qualitative interview methods and involved in the reflection process.

Language barriers often play a major role in the everyday lives of people affected by deskilling. Their ability to learn German after arriving in Austria, but before they start working, is often determined by their socio-economic background: "People from Romania in particular are often forced to earn money immediately and are therefore tempted to accept a job that does not correspond to their level of education," reports Anna-Katharina Draxl. For example, they often accept low-skilled cleaning jobs that can be done with little knowledge of German. However, due to the combined high workloads of the job and care work, it is difficult to simultaneously acquire the necessary German language skills to have their professional qualifications recognised. As a result, many migrants are caught in a vicious circle of under-qualification. Even if German is not always officially required for the workplace, it is often required pro forma. This is also the case at universities or international organisations, where English (rather than German) is often the working language.

Structural deskilling

The research team explains that the deskilling process is an interplay between migrants' own agency, institutional framework conditions and labour market structures. Discrimination experienced by migrants is structural and has a function: "We need an economy that doesn't exploit anyone and that works without these hierarchies," says Clara Holzinger. The project therefore aims to contribute to reducing social inequalities and, in particular, unwarranted discrimination.

"As a society, we should ask ourselves whether or not we are actually harming ourselves with this discrimination," states Elisabeth Scheibelhofer. Necessary social changes would include making this discrimination visible, valuing multilingualism and diversity—in the labour market, in society as well as in research itself—and much more discourse about it. Actors in institutions such as the AMS, but also employers and recruiters, need to be made more aware of discriminatory mechanisms (including those with regard to language). At the same time, bureaucratic barriers must be removed and support measures such as language courses—including at higher levels—as well as information and support services for further training and requalification opportunities, should be made more widely available. The project aims to contribute to these objectives. In addition to academic publications and presentations, the research team therefore considers lectures and publications aimed at a broader audience and institutional stakeholders a central concern. A lecture series dedicated to the topic of multilingualism in research was also organised during the Austrian 2023/24 winter semester. The results from the study will also benefit labour market policy stakeholders such as the AMS, which could, for example, use the findings to provide more resources for multilingual services for job-seeking migrants.

Key data on the project

- Title: DeMiCo – Investigating the social construction of deskilling among 'new' EU migrants in Vienna

- Project period: 05/2021 – 04/2025

- Research team: Elisabeth Scheibelhofer, Clara Holzinger, Anna-Katharina Draxl

- Translators and interpreters:

Czech-German: Ladislava Baxant-Cejnar & Michaela Kuklová

Hungarian-German: Anna Ledó & Izabella Nyari

Romanian-German: Cinzia Hirschvogl & Corina Niţu - Department: Department of Sociology

- Funding: Austrian Science Fund (FWF)

Publication

- Scheibelhofer, E., Holzinger, C. & Draxl, A. (2023). Confronting Racialised Power Asymmetries in the Interview Setting: Positioning Strategies of Highly Qualified Migrants. Social Inclusion, Vol. 11(2), pp. 80-89: doi.org/10.17645/si.v11i2.6468